The Power of Knowing One's Past

Knowing where we have been is how we know where we will go next.

Services such as 23andMe have gained such popularity in recent years that they have raised $82.5 million in early December 2020, even though layoffs have happened earlier in the year. In October 2012, Ancestry.com, another popular DNA testing company (who has been profitable since 1996!) was sold for $1.6 billion. The global interests in the horoscope, dated back thousands of years, further confirm our shared obsessions over where and when we come from, and the meanings of such information. With the current accelerating rate of technology and increasingly lowering costs, it’s easier than ever to expand our self-knowledge of the past.

It’s certainly common for someone to be interested in genetics when it’s for a medical reason. And yet, not only knowledge of ancestry allows us to prevent certain genetic diseases early, but it’s also a window into how we become who we are and how we connect with others. By making connections with others from similar backgrounds, we have the opportunities to gain better self-acceptance, which consequently leads to improvement in life quality.

10,000 years ago, the concept of family trees began to take hold in our shared consciousness. Since we’re more likely to trust those we share our genes with (a phenomenon known as kin selection), family ties make it possible for us to receive support from people in different social groups — a support network beyond our immediate family, which increases the survival odds for the whole community.

Besides being “a biological given”, relatedness is also “a social construct”. Sharing a linage means sharing stories and subcultures. In the meantime, our perceptions of the world could be challenged by those we may not interact with otherwise. According to a study, children with a strong “family narrative” grow up with better emotional health. The more knowledge children gain about their family, the stronger their sense of control over life, the higher their self-esteem and the more successfully they believe their families functioned.

“Yes, it is true that knowing your heritage doesn’t fully define you, but it can help you find your starting point in life. It can help to determine what you have the potential of becoming.”

— Valerie Soleil, Bachelor’s Degree in Law and a B.A. in Psychology

In her essay for The Guardian, Rebecca Hardy stated three types of family stories: the ascending one (“We built ourselves up out of nothing”), the descending one (“We lost it all”), and the oscillatory one (“We have had our share of ups and downs”). She reasoned when talking about our family stories, it’s crucial to tell the negative stories along with positive ones because children’s emotional health depends on these so-called “bad stories”, which provides them with a framework to be more emotionally resilient as adults.

Our biological family plays an essential role in how we progress in life. Sadly, in this Informational Era, it’s not uncommon for us to be separated from much of our family: our tribes have gotten smaller than ever before. The negative psychological effects of not knowing one’s past can be observed most clearly in adopted children, people of the LGBTQA+ community and Bla(c)k community.

Adopted children, who were separated from their “natural clan” at an early age,often describe a major part of their identity missing, psychologically experiencing a “genealogical void”. Commonly, this results in adoptees having an urge to seek out information about their biological parents later in life.

Learning about one’s past is even more tragically challenging to navigate for the African and Indigenous communities. In countries such as the US, Canada and Australia, Bla(c)k people run into a “genealogical brick wall” due to their ancestral lines being erased. Furthermore, Bla(c)k people continue to suffer from the continuous oppression and appropriation of Bla(c)k Culture to present days.

Having a good relationship with family also means a better chance of gaining and retaining wealth. Compared their hetero counterparts, queer youths are at least twice more likely to be homeless, leading to worsened financial (and emotional) support, which consequences could last a lifetime. When a person is cut off from their family either by external or internal causes, it becomes more restricted, if not impossible, for them to access the wealth to which they would have been entitled.

Vietnam has been in the global news cycle more often in recent years, almost always in a more positive light compared to a few decades ago. As someone who was born and grew up in Vietnam during the transitional period after the Vietnam War, I believe this “miraculous” transformation is a by-product of not just a different way of governing than most of the world (including other Communist countries), but also because of what we learned from our ancestors, passing on through thousands of years.

For most of history, most Vietnamese people were illiterate. Thus, knowledge has mostly been through verbal teachings. Because of Vietnam’s unique geography, the country became a melting pot of culture influenced mainly by the Chinese Domination of Vietnam (thought to start from 111 BC to 907 AD and briefly resumed from 1407 to 1427), the Indigenous Culture of the Champa Empire in the South (which was suppressed in the 19th century by the Nguyễn dynasty), and Western influences by the French and Americans during the subsequent wars from the 20th century.

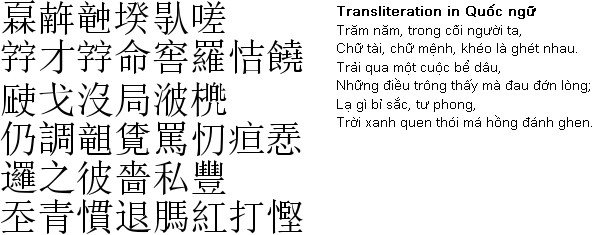

For example, the Vietnamese language originated from Chữ Nôm (meaning: Southen Script), which was developed in the 10th century but had never been used for official purposes except for the two brief periods between 1400–1407 and 1778–1802 under the Hổ and Tây Sơn dynasties, respectively. The Vietnamese language we know today (Chữ Quốc Ngữ) uses the Latin Script and diacritics to signify tones, adopted by French colonists. The most common religion or belief system you find in Vietnam is folk religion, a combination of Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism. Since Vietnamese folk religion is not an official or organised religious system, completely decentralised, it is more diverse and fluid than other significant religions practised worldwide.

A rich history filled with stories of both triumphs and defeats has left the Vietnamese people with much wisdom for everyday life. While militant victories, including the three victories against the Mongolian Empire, give my people a sense of pride, there is a long tradition of using literature to circulate a more resistant type of knowledge. Our folk wisdom shows up in the way we talk, walk, and worship.

I’ve benefited from both traditional teachings and scientific knowledge from the West. This could not be said for war-torn refugee families who fled and have not been connected to their home country and ancestors. Above all, I’m grateful I spent my early years in my home country, with my people, despite the hardships I faced in my youths. I was there for a culture-rich — and raw; Vietnam, which has become harder to find in this increasing capitalistic world we all share.

(And no, Vietnam is not perfect. It got a long way to go as a country. But at least as Vietnamese people, we got thousands of distilled wisdom within us. Globalisation also makes it more challenging to maintain traditional culture and knowledge.)

This recognition and acceptance of who I am and where I come from have been a new thing. For years, I outright rejected my personal and family history. I rejected the Confucian society I was brought up in and its heteronormative construct. It wasn’t because I wasn’t proud of my heritage or ashamed of the “colour” of my skin. Being queer when and where being different was a mortal sin, I struggled with embracing the same community that had rejected me and who I am as a person. Since they didn’t want the real me, I didn’t want to do anything with them either.

My belief system got shattered. For most of my 20s, I felt like I was standing on sands. I was lost. I felt disconnected, not just with who I was as a person but also with the world. After moving to a Western country, I frantically looked for something, anything to fill the emptiness homophobia and transphobia has left me with. (Spoiler alert: I am now found, after like, um, a decade).

Marginalised people are more at risk of discrimination and rejection from their “clan”, which led to the rise of chosen families and online communities to find solace and support. We bond through the stories of the pain we endure. Minority trauma is real, no matter how much some people want to deny and ignore it.

I am lucky. I know I’m much luckier than some of my peers. I’ve achieved some successes since the day I came out, and I found a way back to my roots. I have a bright future ahead of me (or so I hope). Above all, I’m grateful for where I am. However, I’m still learning to exist in contradictory spaces, of painful past and hopeful future.

In the worst moments of my life, ancestry and history gave me tremendous strength — not just what I inherited but also what I can make out of it. I would not be writing this without reading my grandma’s poems or learning about my mum’s dream of being a writer in another life. After all, as Charles Darwin first realised, the entire natural system is “founded on descent”.

“We all feel stronger if we are part of a tapestry [...] One thread alone is weak, but, woven into something larger, surrounded by other threads, it is more difficult to unravel.”

— Stefan Walters, Family Therapist

Seeking self-knowledge is a lifelong journey. The first step is to talk to your parents about their pasts; how they became who they are today. Maybe check out the old family photos tucked away in your family home and find out more about where, when, and how they were taken. And don’t ignore any records available to you, namely pedigree charts, death certificates, and obituaries.

However, since not everyone has access to the family’s records (and I’m so sorry if this does happen to you), a DNA test could potentially provide some insights. A piece of paper explaining your genes may not have the answers to all your questions, but it allows you the possibility for more. Beyond our family, the more knowledge of the world we attain, the more empathy we develop, and the easier we can connect to others. And sometimes in between being with others, we find ourselves.

Whoever you are, it’s my hope you’ll find yourself. And then, your people.